As the high-stakes drama in Crimea played itself out from the end of February through March of this year, one can almost imagine the dismay of the liberal Institutionalist true-believers over the unilateral Russian action, with the suitably grim gallery of realist thinkers nodding sagely to each other as yet another apparent confirmation of the inherently anarchic nature of the international system was displayed for the world to see.

Anyone then following the course that events surrounding the Ukrainian instability and subsequent Crimean crisis is well aware of the rapid pace with which events moved.While much and more has already been written on the subject (although analysis seems to have dropped off as fresher crises have arisen), including a bevy of historical analogies with varying degrees of suitability or usefulness for decision makers and public analysis. Professor David Carment wrote at length and in great detail on the specific dangers of policy making through analogical shortcuts, and those of us at NPSIA who has studied the process of policy-making is well aware of the pitfalls of cognitive shortcuts and historical analogies in foreign policy making.

Now, having said all that, I’m afraid I’m about to indulge in the sin of historical comparison myself in order to draw attention to the daring gambit of presenting the international community with an apparent fait accompli (as well as in an effort to get some mileage out of my undergraduate minor in History).

Over a century ago, there was another regional power in Eastern Europe that was no longer the dominant entity that it once was, one that was faced with declining authority in its sphere of influence.

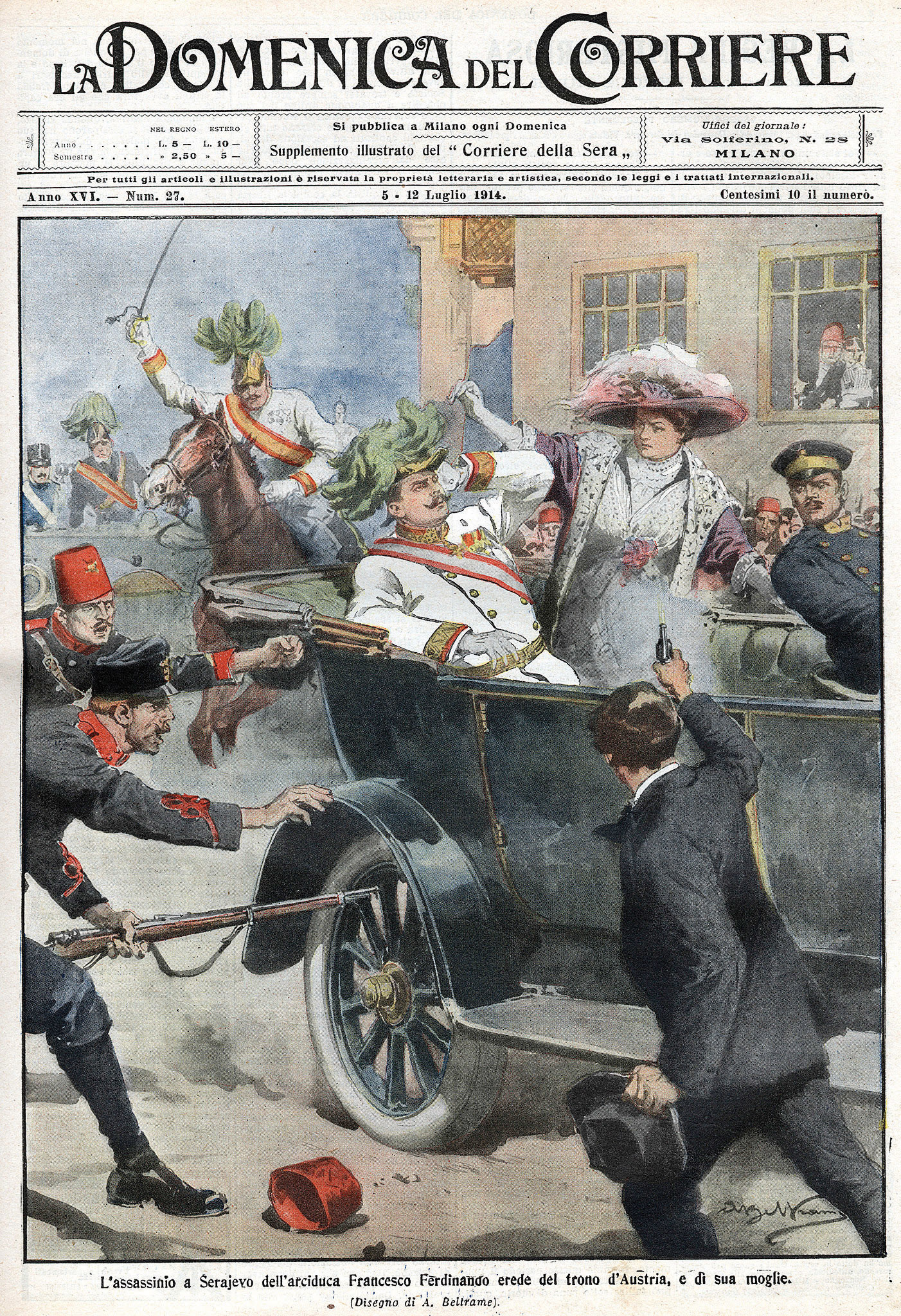

The Austro-Hungarian Empire was faced over the first decade of the 20th century with a particularly troublesome thorn in its side, a rising Serbia with ambitions of expanding itself into a “Greater Serbia”. Austria-Hungary gained firm backing from Germany in any conflict against Serbia on the basis that it would utilize the June 28th 1914 assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand as the pretext to swiftly invade and irrevocably diminish Serbia’s ability to challenge Austria-Hungary in the region.

This was based on the idea that a rapid presentation of an unacceptable ultimatum to Serbia, its inevitable rejection, and the resulting crushing Austro-Hungarian action against Serbia would present the European powers with a fait accompli of Serbia’s invasion and defeat. However, Austro-Hungarian dithering and debate over the exact course of action to be taken stretched out over July 1914 providing the other European powers, particularly Russia and France, time to consolidate their positions and become somewhat aware of the Austro-Hungarian plot. Thus when the ultimatum and rejection came in late July, followed by the declaration of war by Austria-Hungary on July 28, Russia had already given ample assurances to Serbia and the swift, neat presentation of a fait accompli was doomed to failure, and Europe was plunged into the First World War through the ensuing tangle of reinforced alliances.

In comparison, Russia’s actions following the removal of Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych on February 22 and his subsequent flight were swift and decisive. On February 28th, statements from Russia affirmed that they had moved troops into the Crimea ostensibly to protect the “Black Sea Fleet’s positions”. This came alongside reports of unmarked troops popping up throughout the Crimea, wearing Russian uniforms (without insignia), in Russian military vehicles, with Russian weapons and kit, speaking (unsurprisingly) Russian, which, however, Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov denied were Russian troops, claiming instead that these armed groups were autonomous Crimean self-defense forces (albeit extraordinarily well armed ones).

What this allowed Russia to do, was to change the reality on the ground and exert its will militarily while the international community was busy discussing the situation. The lack of identifying insignia on the troops within Crimea further muddied the issue, providing enough confusion and debate among those observing and seeking to condemn Russia that Russia was largely able to carry out its fait accompli as the international community muddled through the crisis casting about for reliable information.

Further, the disruption of Ukrainian media and select officials’ broadcasting and public relations capability through cyber-attacks earlier this month would seem to play into the idea that Russia, or pro-Russian elements within Crimea (who would have to have the advanced technological know-how and capabilities) were seeking to dominate the dialogue and impede the Ukrainian governments’ ability to provide a counter-narrative to that coming from Sevastopol and Moscow.

All of which culminated in the Crimean Referendum and subsequent secession from Ukraine on Sunday, March 16, of which Professor Carment has again, already written. Monday the 17th, Russia recognized Crimea as a nation, and on Tuesday the 18th, Crimea’s return to Russia was formalized in treaty, finalizing the course of events set in motion in late February by Russia. While it is tempting to address the possibility that this was an autonomous Crimean movement, it is impossible to see events taking place the way they did without Russia acting as it did, with the arrival of troops on the ground (whether they were Russian troops, or “self-defence forces”, they were clearly displaying a level of command and control only attributable to Russia), there was little interested third-parties could do, with Western countries immediately ruling out military intervention when these troops first appeared in greater numbers.

In contrast to the 1914 case, the speed with which Russia moved, and the ensuing confusion about events on the ground, prevented the international community from producing a coherent cohesive reaction, as well as from offering Ukraine more than merely vocal support. Four weeks later, and it would appear that the most obvious end goal of securing the continued use of Sevastopol for the Russian Black Sea fleet was achieved almost without a hitch.

But this is not 1914, and there are prices to be paid for modern military intervention, even for Russia. This will be elaborated on in next week’s post analysing the enormous repercussions faced by Russia following its actions, and highlighting the immediate backlash against the well-executed fait accompli.

Look for Part 2 on Monday, December 8th.

George Stairs is a second year M.A. candidate in the Conflict Analysis and Conflict Resolution field at the Norman Paterson School of International Affairs. He has written on various conflicts before, including extensive research and writing on the possibility of instability in the Middle-East arising from the Arab Spring uprisings.

Featured Photo by Sasha Maksymenko.

Comments are closed.